They Came Before Us – illuminative evaluation

Illuminative evaluation of ‘They Came Before Us’ by Pat Devereaux.

Pat Devereaux is a Journalist, Sub-editor, Production at the Guardian newspaper since 1994. She is an experienced Editorial project organiser, magazine and newspaper production editor, writer, journalist, and researcher.

Imagine sitting in a history class in a British school and that you are a young girl of colour… Imagine that you have been born here and that your parents have made this country their home. You feel part of the community and you feel comfortable and settled in your home until you attend school. Then you begin to learn from your history lessons that you don’t belong, that you have never been a part of this country’s history. How alienated and disengaged would you feel?

This was the overwhelming feeling of many of the BAME (Black, Asian and Ethnic Minority) young women I spoke to before they embarked on an explosive art installation, They Came Before Us: ‘Can’t Be What You can’t See’. These women were curious about where they fitted into British culture. They did not see themselves represented in the history books. Then they began exploring the issues of an eradicated black history.

It is known that black people have lived in Britain since early colonial times and there is plenty of evidence that Africans were residing in the country in their numbers even before the 15th century and in Roman times. However, this history appears to have been deliberately swept under the proverbial carpet.

One cannot ignore the current political mood which makes this exhibition most relevant.

At the Brit Awards recently, the South London rapper Santan Dave documented different angles of current British racism, he highlighted how people of colour are often denied. Mass incarceration? Not racist! Grenfell? A “tragedy”, and the survivors still haven’t been rehomed and compensated. Windrush deportations were seen by Theresa May’s government as an administrative error but now resumed under Boris Johnson’s government. Meghan in the royal family? We’re not racist; we just don’t like her, says the media. Dave’s statement was simple but also radical: he told the state that, yes, it is in no uncertain terms racist.

Looking ahead Boris Johnson’s Britain may mean trouble for many BAME Britons. Mass deportations, a regressive drug policy, unfair sentencing and a police force armed with tasers and stun guns continue to threaten black British life. With the recent deportations, we are seeing how the system targets black communities, and immigrants regularly. To paraphrase British journalist and author Reni Eddo-Lodge, we live in a culture where there’s lots of racism but no racists.

British Nigerian author, David Olusoga, who has written a book called: Black and British: A Forgotten History, says most of black British history has been “forgotten”: The subject, he argues, has been mostly excluded from the mainstream narrative of British history. Why it should be forgotten, and who might have forgotten it might make us all ponder since the denial of black British history by those who should know better could be considered racism.

Olusoga reminds us that Britain’s “island story” cannot be isolated from that of the rest of the world and certainly not from Africa and other parts of what was once the British empire.

There is a feminist narrative which needs to be addressed in British history too. Not only has black men’s history been forgotten, so has the experience of women of colour. Often the experiences of mainly white British women are generalised to be representative of all women. Yet the limited data we do have shows that the experiences of women from ethnic and religious minorities, disabled women, LBT (lesbian, bisexual, transgender) women, and women of different ages and backgrounds differ widely. This project highlights the experiences and outcomes of women with different characteristics. That is why this installation assembled by 50 young BAME women is so powerful and relevant.

“All we learned about in school was the slavery of black people in the US. We learned a bit about black leaders in other countries but nothing about us in the history of Britain. So we were naturally curious about where the women like us were,” said project coordinator, Sarah Buller.

[carousel_slide id=’9420′]

How the project came about:

This project emerged in the past year, under the auspices of Collage Arts. Two young BAME women, Sarah Buller and Dowa Ojarikre, who met at work in 2014 on a separate project to get young people into jobs, initiated the idea. They applied for heritage lottery funding for their new project outline and heard back from the funders who loved the project. They got their funding.

So the pair began planning and doing paperwork. They managed to gather together 50 young BAME women to participate in their project in Wood Green, London. The two coordinators came up with the idea after seeing the Tate Modern exhibition “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power.” They wanted to create a British project that explores the social, cultural and political agency of women of colour, as they navigate historic legacies of colonialism, independence, migration and the contemporary global socio-political climate, through performative actions that engage with historic spaces, archives, and collections.

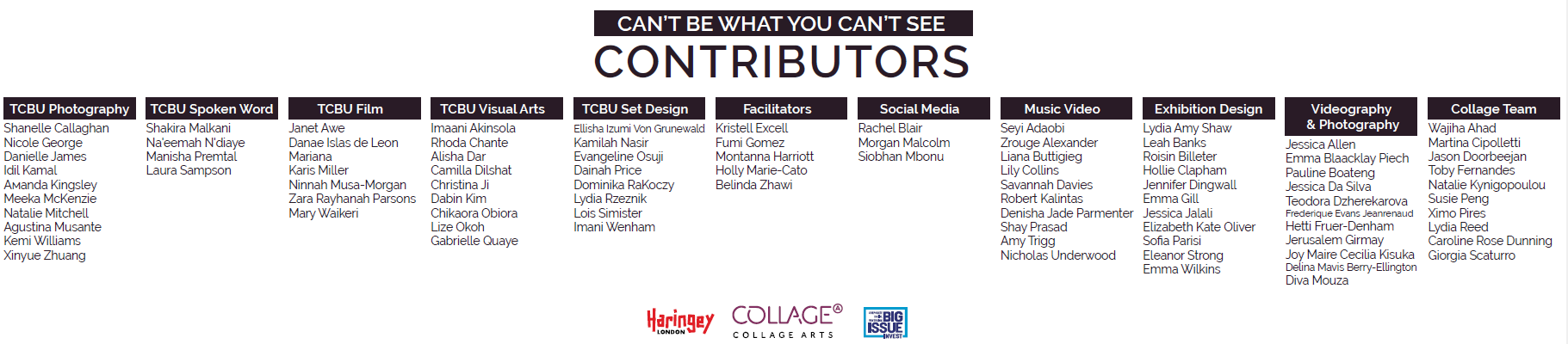

They selected their 50 “BAME BABES” for the photography, spoken word, filming and set design. Met up with them twice a week. “We created little communities for the creative projects,” said Sarah and Dowa. Finding a space that was diverse enough and central enough for the exhibition was difficult. They finally secured a venue at the Old Truman Brewery.

The group of 50 women in the workshops narrowed these broad themes down. They set the tone for a modern retelling of 750 years of British history to include five women of colour. The resulting exhibition called Can’t Be What You Can’t See has re-imagined a future where women of colour are acknowledged. It is a searing, illuminating, relevant inquiry into what it is to be a woman of colour in Britain today.

“This project and exhibition will hopefully help empower BAME women in their everyday life and allow them to better understand their identity. While also encouraging the wider community to learn something new,” said Dowa Ojarikre

About the artwork

The immersive installation They Came Before Us presents a contemporary set built as a young woman’s bedroom and bathroom. Included in the set are films, podcasts, storytelling, and print media. There is a strong educational factor. These young creators enjoyed researching the fascinating stories of five prominent BAME women who have been whitewashed out of British history. They have brought them back to life through photography, film-making, acting, storytelling, and set design. They have also spread the word through social media using Instagram, podcasting, and Twitter.

The bedroom set appears on the surface almost like the scene of a detective story which the viewer then has to explore. There are clues: photographs, posters, audio and visuals relating to the forgotten women and their place in history. The viewer slowly realises this installation is a takedown of the establishment’s selective and self-congratulatory culture of remembrance. It is a multi-media project, which succeeds on so many levels. The subtext is the backdrop of this country’s failure to understand how inherent racism continues to result in obliterating the past.

How I came to be involved as an external evaluator

As a journalist and production editor at The Guardian, I first came into contact with Collage Arts over 20 years ago and I have watched the charity transform into a leading Arts Development Agency which has changed the community through its art spaces and support of creative people of all ages. I’m pleased to see Collage Arts has also survived the encroaching developers in the area.

I met Manoj Ambasna and Preeti Dasgupta on many occasions while attending exhibitions and music events in Woodgreen’s periphery of warehouses and office blocks. I have watched Manoj’s and Preeti’s passionate and tireless vision for Wood Green grow and develop into a vibrant creative hub and a key artist community in the city of London. They are bringing life to dead buildings, degenerate areas and hope to broken communities.

The atmosphere is that art and creativity are the oxygen of a city. We need creatives to revive our flagging spirits. With all the current political, economic and environmental turmoil we will need areas and projects like this all the more.

I see this project as a significant educational building block in the artists’ creative community in Wood Green. I also see it as extending much further. Hopefully touring schools and museums throughout Britain.

Before I first saw the project I was told a bit about it. In the past year, 50 BAME (Black, Asian and ethnic minority) women have been engaged in workshops at Collage Arts creatively responding to the lives of five historical BAME women they chose to see in their view of British history. The result is an exhibition called: Can’t Be What You Can’t See, which has re-imagined a future history where women of colour are represented.

My first visit to this project was to see the installation physically taking shape in the former Wood Green Post Office, now Collage Artspace 4. I was not sure what to expect. It was chaos. The room where it was evolving was a hive of activity, buzzing with adrenalin and excitement. These groups of young women were inspired and industrious: Hammering away at bed frames; Moving structures; Laying bathroom tiles. For most, it was a completely new experience to see their ideas materialise. Young women were flicking through magazines, staring at and discussing videos, chatting on microphones, editing films and hanging up clothes in a wardrobe – they were inspired.

I spoke briefly to the project curators, Sarah Buller, has a background in visual communication and creative arts. She works at Collage Arts. Dowa Ojarikre is the ideas person: “I like developing ideas, forming them and materialising them. I think I am a more of a strategist and planner.” They were both distracted by what needed to be done in the next few days. Our meeting was a few days before their debut exhibition was to be installed in the Old Truman Brewery in East London, and they had deadlines to meet.

Essential knowledge:

The two young curators gave me a brief outline of their project. The feeling I gained from that encounter was one of excitement at the idea that these young women could change history in Britain through their exhibition. Not only can they change history but they have created a fun, engaging, immersive experience for young people in the UK and especially BAME people who will then be able to see themselves represented in history.

The project relates to history and how it is presented in the education system in this country. The question they were asking is: Why have we been studying history at school and never seen anyone like ourselves in the history books? Why are there no BAME women in British history? They then set out on a journey to find them.

So who were the women they found on their journey back in time? Their Detective work shone a light on these five women:

Lilian Bader (1918 -2015) – one of the first black women to join the Royal Airforce at the outbreak of World War II. Workshop leader Sarah Buller said: “This was a woman who was born in Liverpool raised in a convent from the age of nine when she became an orphan. She was fired from her job in a canteen because of her race. But she managed to get trained as an aircraft instrument repairer and became a leader aircraft woman in the RAF.”

Queen Philippa of Hainault (1310-1369) – The women bringing this story to life were excited by the idea that she was England’s first black queen. She was an accomplished woman, Queen’s College, Oxford was founded in her honour. But her story has been whitewashed and her accomplishments have not been given the coverage they deserve.

Catalina de Cardones, lady-in-waiting to Catherine of Aragon (1492- 1531) This story was enjoyed by the photography team who had studied the Tudors. They thought they knew about Henry the Eighth but within the court was a prominent, black woman advising and supporting his queen. The nature of her role would have meant that Catalina would have been treated as a noblewoman.

Seaman William Brown (1790 -?) was more enigmatic. This is the story of a black woman who dressed as a man to join the navy, a pretence she is believed to have kept up for 11 years. The group tracing Seaman Brown were impressed by her boldness and courage, at a time when woman have very few career opportunities open to them. The exhibition celebrates her time on HMS Queen Charlotte.

Zaha Hadid (1950 -2016) an Iraqi born architect, moved to London (later becoming a British citizen) and enrolled at the Architectural Association School of Architecture. Her work was said to have liberated architectural geometry, one quote described her as “the queen of the curve”.

My first visit to the exhibition in The Old Truman Breweries East London

On 2nd November 2019 I attended the debut exhibition of “They Came Before Us: ‘Can’t Be What You Can’t See” at 14 Hanbury Street E1 6QL, just off Brick Lane.

In a small gallery on the street Dowa Ojarikre stands inviting people in. The set is almost like the scene of a modern detective story. The room is dimly lit as one enters, then my eyes adjust. The room is surprisingly inviting and tactile. It is an intimate space, a bedroom.

One can determine it is a young woman’s bedroom and there is a bathroom at the far end. The viewer is invited to explore and interact. There is a flickering screen with videos. There are headphones on the bed. There is an open wardrobe with a film showing inside amidst the clothing. A cluttered dressing table with a magazine. Idyllic posterboards of black ladies in classic Tudor dresses. Postcards pegged up on a line across a wall. The bathroom with tiles and exposed copper pipework which pipes audio stories is an interesting touch too. A large sound box space covered in white and pink fur with the words BAME BABES inscribed above a window. This is where the podcasts take place.

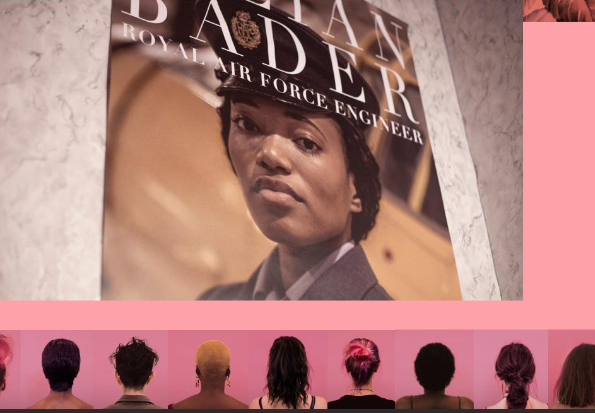

A poster shows a smart young black woman wearing an RAF military uniform. One can sit at the cluttered dressing table and flick through the magazine and read the story of Lilian Bader (1918 -2015), she was one of the first black women to join the Royal Airforce at the outbreak of World War II. Workshop leader Sarah Buller said: “this was a woman who was born in Liverpool raised in a convent from the age of 9, when she became an orphan. She was fired from her job in a canteen because of her race. But she managed to get trained as an aircraft instrument repairer and became a leader aircraft woman in the RAF. The group of visual artists celebrating her life posed the question, What would it have been like if Lilian Bader had been included in the mainstream media?”

Then one moves to the bed on which are placed headphones where one can listen to the stories and poems inspired by the award-winning Iraqi born architect, Zaha Hadid (1950 -2016). In 1972 Hadid moved to London (later becoming a British citizen) and enrolled at the Architectural Association School of Architecture. Her work was said to have liberated architectural geometry, one quote described her as “the queen of the curve”. There is video footage of her buildings on a computer screen nearby. Despite global fame, she initially struggled to find recognition in the UK. Throughout her 39-year-long career she built just a handful of projects in the country where she chose to open her office back in 1979. Hadid’s nadir was in 1995 when Cardiff rejected her futuristic opera house design, despite the fact that she beat 268 rivals in a competition. The design was so radical that she was asked to submit again for a second round, which she again won. The opera house was ditched and Hadid was bitter. She claimed she was the victim of xenophobia, racism, misogyny, you name it – and she had a point. So many people didn’t like her, thought she was too big for her booties, an outsider, an interloper in a male preserve. In 2004 Hadid was awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize, considered the profession’s highest honour. She was the first woman to receive the award. In the mid-2000s she finally received a full-scale commission in the British Isles, for a cancer-care building called Maggie’s Centre in Fife, Scotland. In a Guardian interview in 2010, journalist Simon Hattenstone asked Hadid, What Prince Charles said to her when he presented her with the CBE? “He asked me if I practise in Britain,” she replied. In 2012 she was made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE).

On another wall in the bedroom is a classical poster in dynamic colours of a black Tudor lady and there are postcards depicting the idyllic life of the Iberian moor Catalina de Cardones, lady-in-waiting to Catherine of Aragon (1492- 1531). This story fascinated the photography team. Nearly all had studied the Tudors in school and they thought they knew about Henry VIII. But they had never heard that within the court was a prominent, black woman advising and supporting the queen for 26 years. The nature of her role would have meant that Catalina herself would have been treated as a noblewoman.

Then we come to the film of Queen Philippa of Hainault (1310-1369) who was England’s first black queen and mother of “The Black Prince” Edward, who died in battle. The women on the project researched her background and found a full description of her features given by Bishop Stapeldon who was sent to look at her as a suitable bride by King of England Edward 11. It is clear from the vivid description of her that Philippa is a young “brown-skinned” girl. Four years later this young swarthy woman was betrothed to his son Edward 111 and at the age of 15 in 1328 she was married to him. The sculpture for her tomb is in Westminster Abbey. But nobody in modern history books mentions that she was black. I read recently on a website that her son Edward of Woodstock was called the “Black Prince” because of his black armour and on another that he was called the black prince because of his battle tactics. But surely the most simple reason is that he was, in fact, dark like his mother? Or was that a step too far for the English historians? He is after all buried in Canterbury Cathedral.

In the bathroom, we find the history of the last woman who is the most enigmatic Seaman William Brown (1790 -?) (birth name unknown) was an “African” who joined the Royal Navy under a man’s name in the early nineteenth century. It is undisputed that she was a sailor of HMS Queen Charlotte, but historians have reached varied conclusions about her service record. According to the Times of September 2nd, 1815, Brown was an experienced sailor. She had served in the royal navy for upwards of 11 years and appears to be about 26 years of age says the report. “She says she is a married woman. and went to sea in consequence of a quarrel with her husband.” She assumed the name of William Brown on the HMS Queen Charlotte for many years as an able seaman and had been promoted to “captain of the fore-top”, in charge of other sailors assigned to that particular part of the ship. She was discharged on 19 June 1815, “being a female”. An audio recording comes through the copper piping in the bathroom and tells us her secrets and there is an embroidery and a towel which are further clues to her role in history. Charles Culliford Dickens, son of Charles Dickens, picks up the story and reports it on April 6, 1872. He knew William Brown’s story made good reading: She was female, black and had romance. She appeared patriotic, fighting for king and country and yes she was full of swashbuckling derring-do as she climbed “the rigging” and collected her “prize money. She bore all the qualities of a legendary heroine.

My second experience of the exhibition in Collage Artspace 4 Wood Green.

Visiting the exhibition for the second time in the old Post Office in Wood Green I see more. The setting is similar, the room is a different shape. Pictures and props have moved about a bit. It retains the intimate feeling though. This time I notice the graft that has gone into the setting and finer details. I see the story in the pages of the magazine describing Lilian Bader’s family life. I watch the footage of Zaha Hadid’s extraordinary architecture on the screen. I notice the idyllic beauty and clarity in the radiant blown-up photographs of Catalina de Cardones. I hear the story of Seaman William Brown through the copper pipes. I see the photographs of her binding her chest and look closer at an embroidered piece with the words “Another bloody heavy month with all this bleeding. The seamen will start to think I’m dying in my sleep”. The obvious assumption is that seaman Brown had to hide her femininity from the other seamen. The creators of this project have entered into the lives of these historic women. They have become them. Acted the roles in the films and photographs and entered into the feelings these historic women might have felt. In doing so they have made these women’s lives come to life for the audience.

Interviews with key participants:

Sarah Buller: Project coordinator: I have been employed by Collage Arts for 5 years. My background is in set design. Dowa and I have worked together on other BAME projects. We were inspired by a Tate exhibition called Soul of an Artist to start this project. Dowa came up with the title for this installation They Came Before Us: Can’t Be What You Can’t See. One of the emotions running through this exhibition was disappointment. We wondered why we hadn’t heard of most of these women before. We thought being angry about being excluded from history would not engage our audience. Our visitors’ reactions were so good. They got it and many thanked us so sincerely. We had two local schools dropping in. The first group of schoolchildren loved being able to touch and feel the installation props. The older groups Said they loved it and told us they wouldn’t normally go to exhibitions. Most difficult was getting the concept together. We had to fit all the pieces together and make it work in the space. I loved it in the end and would love to go bigger, say a whole house like this. I feel it achieved its aims and we got people thinking. However, the time was perhaps too short. Many people didn’t see the actual exhibition but heard about it online.

Nicole (Background is Trinidadian and Jamaican) in the photography group: Twelve of us worked on the Catalina story. We went to visit the Black Cultural Archives in Brixton and were talked through her story. We knew about Catherine of Aragon in history but never heard of Catalina. I could tell you about the Victorians and slavery. We never learned about black women in history they were completely whitewashed out. I did a lot of photography on the project and now work for a black-owned hair brand. It was lovely to be around Sarah and Dowa and Like-minded people. I would love this exhibition to appear in museums around the country. The subjects have stayed with me especially the mystery of Seaman Brown.

Shakira (Background is Indian and Caribbean) involved in the spoken word:

“There were four of us who wrote poetry for the exhibition, which was then recorded as spoken word and played on headsets. This was an amazing project to work on, and I really enjoyed working with the team. Taking part has inspired me to write more poetry and soundtracks. This project focussed on the celebration of these women’s lives. People of colour don’t always want to be portrayed as angry, anger is part of a stereotype of people of colour. There is anger and frustration about racism within the UK, but there is also a lot of love, resilience and power within our BAME communities which is inspirational – and is what I felt when collaborating with the other creatives on the project and seeing the whole exhibition put together. It felt powerful that we could tell these stories, which historically, has often not been the case. I would love to see this exhibition displayed again in other parts of the UK. This concept was very valuable in the climate of Brexit.”

Laura (Background is Trinidadian and English) was involved in the spoken word:

“I’d been involved in writing with Collage Arts. I am local to Wood Green. I’ve done review writing and storytelling. and storyboarding. I have a degree in English literature. My favourite part of the exhibition was that it was a set as a young woman’s flat. I knew about Zaha Hadid but I did not know about the lady-in-waiting Catalina de Cardones. I wish we had been able to do more writing. I would love this format to move into schools. We could put the world to right through art. This project inspired me to do more writing. Show more of myself.”

Camilla (Background is Uyghur, northwest of China) involved in the visual arts:

“I found out about this project while looking for art jobs. I live in Herfordshire. I helped with the set design and the postcards. It was amazing to see how it all came together in the end. We didn’t know what the other groups were working on. I worked on the bit with Lilian Bader, the RAF engineer. We went to the RAF museum to find out about her career. There wasn’t anything on her. Lots on the brides of pilots. I went to school in Potters Bar and all we covered was the Slave Trade. I am now studying history at UCL learning about the Silk Road and Ancient Mesopotamia and African history. I would love them to do more with this exhibition. Re-run it or have it travel around the country. My friends attended and enjoyed it. There were a lot of teachers who asked us about the exhibition and asked if we had a website.

Lidia (Background is Polish) involved in the set design:

“This project was recommended to me by a friend. I am based in Surrey so it was a two-hour journey every day to attend. I studied film production with specialisation in Production design and working on this installation helped me gain so much more experience. We researched Seaman William Brown’s story from scratch. We went to Portsmouth to look at the ships and also went to see the Black Cultural Archives. It was an impressive project. My favourite part was the construction of the set. I enjoyed laying tiles and learned so much. I would love to see these women included in the history syllabus. It would be great to see this exhibition move around the country.”

Mariana (Background is Mexican Peruvian) involved in the film section:

“I came across the project while I was looking for internships. I am at UCL studying arts and sciences. I’m doing film studies. So I was involved in the making and editing of the film about Queen Phillipa. 12 of us ended up in that section. We all researched and then pitched our ideas. We researched at the Black Cultural Archives. I enjoyed working on the concept. I was sitting invigilating for one of the exhibitions in Wood Green and a young boy came up and asked me “What is whitewashing?” I would love this to tour. We never learned anything about this at school. It was only at university that I learned about decolonisation. I was drawn to this project. The drive stemmed from anger that we weren’t represented in history but the creativity in the project dissipated our anger. Friends came to the exhibition they thought it was such an exciting concept. Some visitors to the exhibition even thought this was our fantasy and that we had made it all up.”

Feedback from the project:

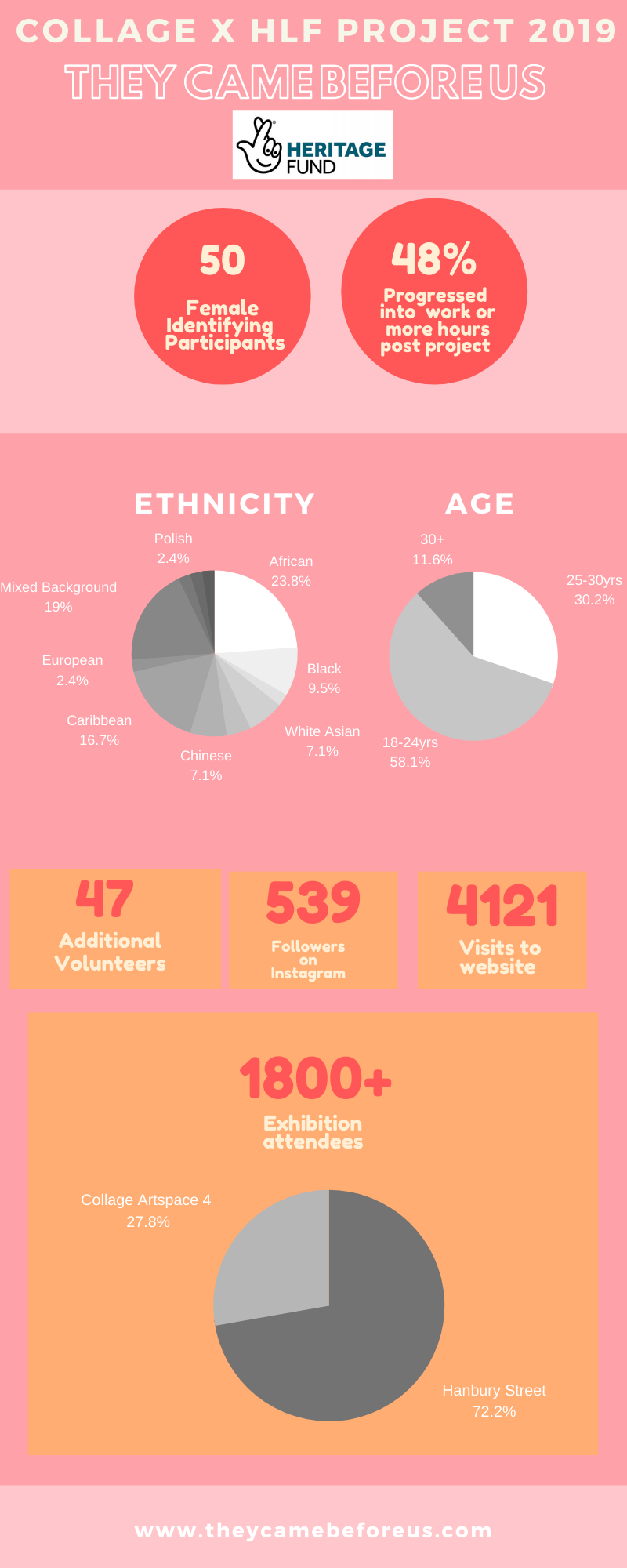

Feedback was enthusiastic and positive in the visitor’s books. People found it aesthetically pleasing and educational. Many loved the inspirational stories of the women. Some felt inspired and emotional… The exhibitions were well attended. Overall there were reported to be 1,800 attendees at the exhibition. About 72.2% attended in Hanbury Street and 27.8% attended at Collage Artspace 4. The exhibition gained 539 followers on Instagram. 97 people were engaged through the project and there were 40 workshop attendees. Ten attendees found jobs through the work. Coordinator Sarah said: Visitors were very positive it was a bit surreal. So many people said “thank you” in a sincere way. Some seemed a bit sad. Many said they would love it to become a permanent structure somewhere.”

Closing summary

As an external evaluator, I feel this project is engaging and relevant in the current climate. I was hugely enlightened by the installation and the authentic clear message it was trying to convey: “To women of colour you are welcome here, can settle here, can contribute to British society and you can be part of this country’s history. Indeed you already are!”. These 50 BAME women who initiated the exhibition must be congratulated and acknowledged for their creative efforts and hard work they put in to make it an inclusive and multicultural exhibition. I think this installation goes a long way toward enabling people to understand racism and sexism in British history. The characters they have chosen as their subjects in the exhibition amplify the voices of young BAME women in this society. Whitewashing history is a divisive tactic but this exhibition explores that and goes some way toward dismantling it. It ensures we see and enjoy the rich tapestry that exists in Britain.

They Came Before Us: A History of Women of Colour in the UK is a project funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund made possible with the money raised by National Lottery players. The project acknowledges the support of the Museum of London, Black Cultural Archives, Feminist Library and The National Archives for their help in accessing source material. The project is run through Collage Arts, a leading arts development, training and creative regeneration charity based in the heart of Haringey’s Cultural Quarter.

ANNEX 1 – Infographic on Project Statistics